How Can a Physical Therapist Help?

The physical therapist is an integral part of the team of health care professionals who help people receiving a total knee replacement regain movement and function, and return to daily activities. Your physical therapist can help you prepare for and recover from surgery, and develop an individualized treatment program to get you moving again in the safest and most effective way possible.

Before Surgery

The better physical shape you are in before TKR surgery, the better your results will be (especially in the short term). A recent study has shown that even 1 visit with a physical therapist prior to surgery can help reduce the need for short-term care after surgery, such as a short stay at a skilled nursing facility, or a home health physical therapy program.

Before surgery, your physical therapist may:

Teach you exercises to improve the strength and flexibility of the knee joint and surrounding muscles.

Demonstrate how you will walk with assistance after your operation, and prepare you for the use of an assistive device, such as a walker.

Discuss precautions and home adaptations with you, such as removing loose accent rugs that could cause you to “catch” your leg on them when maneuvering with an assistive device, or strategically placing a chair so that you can sit instead of squatting to get something out of a low cabinet. It is always easier to make these modifications before you have TKR surgery.

Longer-term adjustments that are recommended prior to surgery include:

Stopping smoking. Seek assistance or advice from your physician on stopping smoking, as you schedule and plan for your surgery. Being tobacco-free will improve your healing process following surgery.

Losing weight. Losing excess body weight may help you recover more quickly, and help improve your function and overall results following surgery.

Immediately Following Surgery

You may stay in the hospital for a few days following surgery, or you may even go home on the same day, depending on your condition. If you have other medical conditions, such as diabetes or heart disease, you might need to stay in the hospital or go to a skilled nursing facility for a few days before returning home. While you are in the hospital, a physical therapist will:

Educate you on applying ice, elevating your leg, and using compression wraps or stockings to control swelling in the knee area and help the incision heal.

Teach you breathing exercises to help you relax, and show you how to safely get in and out of bed and a chair.

As You Begin to Recover

The goal of the first 2 weeks of recovery is to manage pain, decrease swelling, heal the incision, restore normal walking, and initiate exercise. Following those 2 weeks, your physical therapist will tailor your range-of-motion exercises, progressive muscle-strengthening exercises, body awareness and balance training, functional training, and activity-specific training to address your specific goals and get you back to the activities you love!

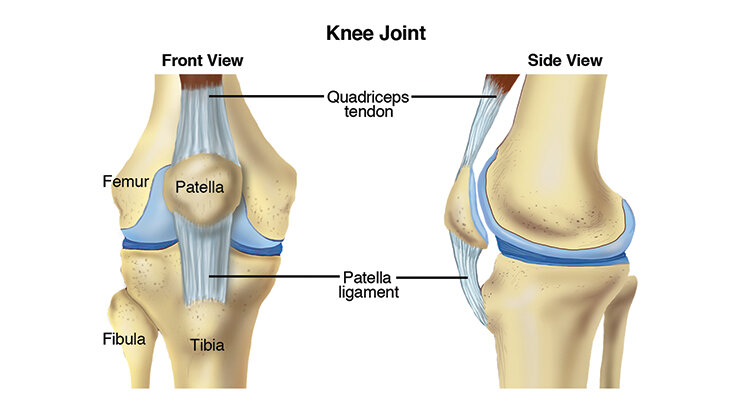

Range-of-motion exercises. Swelling and pain can make you move your knee less. Your physical therapist can teach you safe and effective exercises to restore movement (range of motion) to your knee, so that you can perform your daily activities.

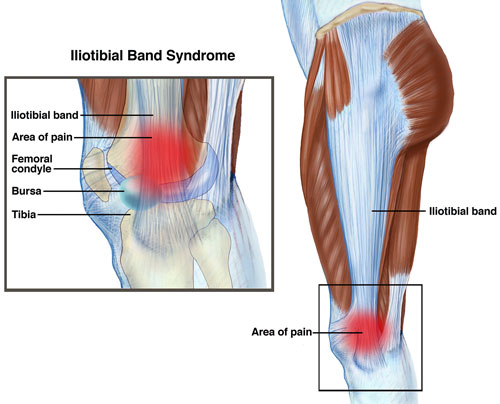

Strengthening exercises. Weakness of the muscles of the thigh and lower leg could make you need to still use a cane when walking, even after you no longer need a walker or crutches. Your physical therapist can determine which strengthening exercises are right for you.

Body awareness and balance training. Specialized training exercises help your muscles "learn" to respond to changes in your world, such as uneven sidewalks or rocky ground. When you are able to put your full weight on your knee without pain, your physical therapist may add agility exercises (such as turning and changing direction when walking, or making quick stops and starts) and activities using a balance board that challenge your balance and knee control. Your program will be based on the physical therapist’s examination of your knee, on your goals, and on your activity level and general health.

Functional training. When you can walk freely without pain, your physical therapist may begin to add activities that you were doing before your knee pain started to limit you. These might include community-based actions, such as crossing a busy street or getting on and off an escalator. Your program will be based on the physical therapist's examination of your knee, on your goals, and on your activity level and general health.

The timeline for returning to leisure or sports activities varies from person-to-person; your physical therapist will be able to estimate your unique timeline based on your specific condition.

Activity-specific training. Depending on the requirements of your job or the type of sports you play, you might need additional rehabilitation that is tailored to your job activities (such as climbing a ladder) or sport activities (such as swinging a golf club) and the demands that they place on your knee. Your physical therapist can develop an individualized rehabilitation program for you that takes all of these demands into account.

Can this Injury or Condition be Prevented?

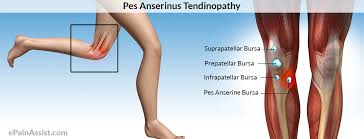

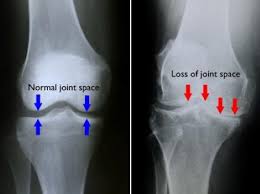

If you have knee pain, you may be able to delay the need for surgery by working with a physical therapist to improve the strength and flexibility of the muscles that support and move the knee. This training could even help you avoid surgery altogether. Participating in an exercise program designed by a physical therapist can be one of your best protections against knee injury. And staying physically active in moderately intense physical activities and controlling your weight through proper diet might help reduce the risk of osteoarthritis of the knee getting worse.

Real Life Experiences

Carmella is a 67-year-old grandmother of 3 who has had osteoarthritis in her right knee for a few years. She used to take care of her grandchildren after school each day before her daughter got home from work. Then Carmella's knee became so painful that she could no longer walk up and down stairs or stand for long periods of time. She also had a lot of difficulty getting up from a chair. She had to tell her daughter that she couldn't take care of her grandchildren anymore. She decided to see a physical therapist.

Carmella’s physical therapist began her first session by asking detailed questions about her knee, such as what other treatments Carmella had tried and the outcomes of those treatments. Carmella said she had seen an orthopedic surgeon who had suggested injections, which helped reduce her pain for a period of time. Her physical therapist then asked her how her current knee pain affected her ability to do the things she wanted to do. Carmella said it made her unable to care for her grandchildren, participate in a regular walking program for fitness, or do the things she enjoyed for recreation.

Her physical therapist then took some measurements of her knee range of motion and strength and conducted tests to get a better idea of what was generating her pain. He suggested that she consult with an orthopedic surgeon. After carefully reviewing her condition and learning about her previous treatments and current activity limitations, the surgeon suggested it was time for a total knee replacement. Carmella agreed. The surgeon scheduled the procedure for 1 month later.

To prepare for surgery, Carmella’s physical therapist taught her strengthening and stretching exercises, showed her how to use crutches following surgery, and advised her on preparing her home environment to make it safe post surgery.

The first day after her surgery, a hospital-based physical therapist came to Carmella's room to begin a gentle recovery program. She showed Carmella how to bend and straighten her knee and how to tense and then relax and release her knee, calf, and hip muscles to strengthen them. She then helped Carmella practice sitting at the edge of her hospital bed and standing up using crutches.

The second day after surgery, Carmella started walking with crutches with the physical therapist’s assistance, putting a little weight on her right leg. The physical therapist also instructed her in some gentle leg-strengthening exercises.

On the third day after surgery, Carmella was able to walk using her crutches, monitored by the physical therapist but without her help, in the hospital hallways and up and down a few stairs. Her physical therapist designed an at-home exercise program just for her, and taught it to her. Carmella was discharged home with a pair of crutches.

Once Carmella returned home, a home-care physical therapist regularly visited her at her house to continue her rehabilitation. As she improved, he prescribed more challenging exercises for her that added weights for strengthening. Carmella also began to practice walking with a cane instead of her crutches.

Two weeks after her surgery, Carmella began going to outpatient physical therapy. Her pain progressively decreased and she had noticeable improvements in her knee range of motion and the strength of her lower body. She and her physical therapist developed a plan that would help allow her to get back to her recreational activities as well as allow her to care for her grandchildren.

A few weeks later, Carmella felt hardly any pain in her knee. She could walk without using a cane, but still needed to use a handrail when going up or down stairs. At times, her knee felt "shaky." She told her physical therapist she was still not comfortable taking care of her grandchildren because of these remaining challenges.

Carmella's physical therapist instructed her in more aggressive strengthening and movement exercises for her hips, knees, and ankles. She also worked with her on improving her stair climbing, balance, and agility. Carmella began to feel more confident walking up and down stairs, getting in and out of her car and driving, and performing other daily activities. She felt that her new knee was much more stable.

A few weeks later, Carmella was able to take care of her grandchildren again! She also joined a health club that offered exercise programs for older adults, so she could maintain the benefits she had gained from her physical therapy.

This story was based on a real-life case. Your case may be different. Your physical therapist will tailor a treatment program to your specific case.

What Kind of Physical Therapist Do I Need?

Although all physical therapists are prepared through education and experience to treat people who have a TKR, you may want to consider:

A physical therapist who is experienced in treating people with orthopedic, or musculoskeletal, problems

A physical therapist who is a board-certified clinical specialist or who has completed a residency or fellowship in orthopedic physical therapy, giving the physical therapist advanced knowledge, experience, and skills that may apply to your condition

You can find physical therapists who have these and other credentials by using Find a PT, the online tool built by the American Physical Therapy Association to help you search for physical therapists with specific clinical expertise in your geographic area.

General tips when you're looking for a physical therapist:

Get recommendations from family and friends or from other health care providers.

When you contact a physical therapy clinic for an appointment, ask about the physical therapist's experience in helping people with TKR.

During your first visit with the physical therapist, be prepared to describe your symptoms in as much detail as possible, and say what makes your symptoms worse.

Further Reading

The American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) believes that consumers should have access to information that could help them make health care decisions and also prepare them for their visit with their health care provider.

The following articles provide some of the best scientific evidence about physical therapist treatment of TKR. The articles report recent research and give an overview of the standards of practice for treatment both in the United States and internationally. The article titles are linked either to a PubMed abstract (summary) of the article or to free access of the entire article, so that you can read it or print out a copy to bring with you when you see your health care provider.

Harmelink KE, Zeegers AV, Hullegie W, et al. Are there prognostic factors for one-year outcome after total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Arthroplasty. 2017 August 1 [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.07.011. Article Summary in PubMed.

Pua YH, Seah FJ, Poon CL, et al. Age- and sex-based recovery curves to track functional outcomes in older adults with total knee arthroplasty. Age Ageing. 2017 August 30 [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afx148. Article Summary in PubMed.

Sobh AH, Siljander MP, Mells AJ, et al. Cost analysis, complications, and discharge disposition associated with simultaneous vs staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2017 September 13 [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.09.004. Article Summary in PubMed.

Bistolfi A, Zanovello J, Ferracini R, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of neuromuscular electrical stimulation after total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017 October 7 [Epub ahead of print]. Article Summary in PubMed.

Otero-López A, Beaton-Comulada D. Clinical considerations for the use lower extremity arthroplasty in the elderly. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2017;28(4):795–810. Article Summary in PubMed.

Loyd BJ, Jennings JM, Judd DL, et al. Influence of hip abductor strength on functional outcomes before and after total knee arthroplasty: post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2017;97(9):896–903. Article Summary in PubMed.

Piva SR, Teixeira PE, Almeida GJ, et al. Contribution of hip abductor strength to physical function in patients with total knee arthroplasty. Phys Ther. 2011;91:225–233. Free Article.

Dowsey MM, Liew D, Choong PF. The economic burden of obesity in primary total knee arthroplasty. Arthritis Care Res(Hoboken). 2011;63(10):1375–1381. Article Summary on PubMed.

Piva SR, Gil AB, Almeida GJ, et al. A balance exercise program appears to improve function for patients with total knee arthroplasty: a randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2010;90:880–894. Free Article.

Bade MJ, Kohrt WM, Stevens-Lapsley JE. Outcomes before and after total knee arthroplasty compared to healthy adults. J Ortho Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40:559–567. Free Article.

Walls RJ, McHugh G, O’Gorman DJ, et al. Effects of preoperative neuromuscular electrical stimulation on quadriceps strength and functional recovery in total knee arthroplasty: a pilot study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:119. Free Article.

Topp R, Swank AM, Quesada PM, et al. The effect of prehabilitation exercise on strength and functioning after total knee arthroplasty. PM R. 2009;1:729–735. Article Summary on PubMed.

Kirkley A, Birmingham TB, Litchfield RB, et al. A randomized trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee [published correction appears in: N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2004]. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1097–1107. Free Article.

Minns Lowe CJ, Barker KL, Dewey M, Sackley CM. Effectiveness of physiotherapy exercise after knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2007;335:812. Free Article.

Moffet H, Collet JP, Shapiro SH, et al. Effectiveness of intensive rehabilitation on functional ability and quality of life after first total knee arthroplasty: a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:546–556. Free Article.

Deyle GD, Henderson NE, Matekel RL, et al. Effectiveness of manual physical therapy and exercise in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:173–181. Free Article.

*PubMed is a free online resource developed by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PubMed contains millions of citations to biomedical literature, including citations in the National Library of Medicine’s MEDLINE database.

Authored by Anne Reicherter, PT, DPT, PhD. The author is a board-certified clinical specialist in orthopaedic physical therapy. Reviewed by the MoveForwardPT.com editorial board.