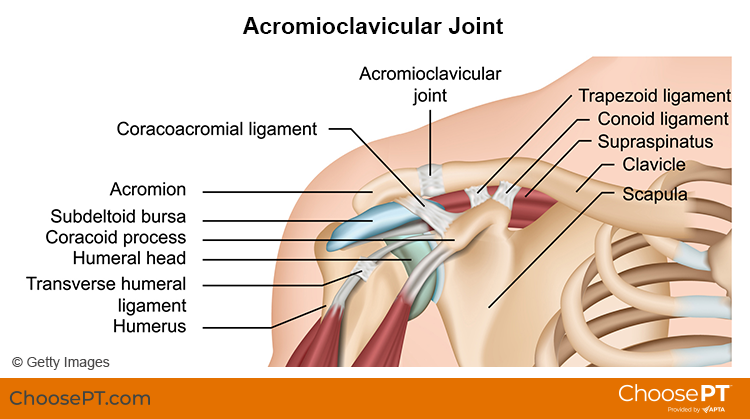

The acromioclavicular, or AC, joint is part of the shoulder girdle (the collar bone and shoulder blade that support the shoulder joint). An AC joint injury describes an injury to the top of the shoulder. It occurs where the front of the shoulder blade (acromion) attaches to the collarbone (clavicle). Most often, trauma, such as a fall directly on the outside of the shoulder, causes an AC joint injury. Overuse (repeated lifting of heavy weights or objects overhead with poor mechanics) also can result in an AC joint injury.

AC joint injuries are most common in people younger than age 35. Males sustain five times more traumatic AC joint injuries than females. Younger athletes who take part in activities like football, biking, skiing, and hockey have the highest risk for this injury.

Physical therapists can identify and effectively treat AC joint injuries, often avoiding the need for surgery.

What Are Acromicioclavicular (AC) Joint Injuries?

There are four ligaments that hold the two bones of the AC joint together. When an AC joint injury occurs, these ligaments are stressed. This stress results in some degree of joint separation. There are two types of injuries of the AC joint: traumatic and overuse injuries.

Traumatic AC joint injury. This type of injury occurs when the joint is disrupted. The ligaments that hold the two bones of the joint together get stretched too far. This is called a shoulder separation. It is different from a shoulder dislocation, which involves the ball-and-socket joint.

Traumatic AC joint injuries are most common in people who fall and land on the outside of the shoulder or hand. Examples include a:

Football player who is tackled.

Cyclist who crashes.

Worker who falls off a ladder.

Traumatic AC joint injuries can range from a mild to severe grade. Grading is based on the amount of joint separation involved. Mild cases can be treated by a physical therapist. More severe cases may require surgery followed by physical therapy.

Overuse AC joint injury. This type of injury occurs over time due to repeated and too much stress on the joint. Cartilage at the end of the acromion and clavicle bones protects the joint from daily wear and tear. Over time, the demand placed on this cartilage may be more than it can endure. The result is an overuse injury that can lead to major wearing of the cartilage and arthritis. Overuse AC joint injury is most common in people who do repeated tasks. Examples include:

Heavy weightlifting (bench and military presses).

Jobs that require physical work with the arms stretched over the head.

How Does It Feel?

With an AC joint injury, you may experience:

General shoulder pain and swelling.

Swelling and tenderness over the AC joint.

Loss of shoulder strength.

A visible bump above the shoulder.

Pain when lying on the involved side.

Loss of shoulder motion.

A “popping” sound or feeling that your shoulder “catches” with movement.

Discomfort with daily activities that stress the AC joint. Examples include lifting objects overhead, reaching across your body, or carrying heavy objects at your side.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Physical therapists can diagnose an AC joint injury through a shoulder exam. Your physical therapist will conduct a full evaluation to find out the degree of your injury and identify all the factors that may contribute to it.

They will begin by interviewing you to learn about your health history. They may be helped by forms you fill out before your first session. The interview will become more specific to the condition of your shoulder. Your physical therapist may ask you questions such as:

How did your injury occur?

How have you taken care of the condition, such as seeing other health care providers? Have you had imaging (X-ray, MRI) or other tests and received their results?

What are your current symptoms? How have they changed your typical day and activities?

Do you have pain, and if so, what is the location and intensity of your pain? Does the pain vary during the day?

Do you have trouble doing any activities? What activities are you unable to do?

This information allows the physical therapist to better understand what you are going through. It also helps determine the course of your physical exam.

The physical exam will vary depending on your interview. Most often it will begin with observing the region of your symptoms and any movements or positions that cause pain. Your physical therapist also may examine other areas of your body that may have changed due to problems with your shoulder function. They may:

Watch you move your arm and shoulder overhead, and while doing other reaching tasks.

Assess the mobility and strength of your shoulder.

Check other regions of the body as needed. This will help to determine if other areas also require treatment to improve your condition.

Gently, but skillfully, feel around your shoulder and the AC joint to find exactly where it is most painful.

Your physical therapist will discuss their findings with you. They will work with you to develop a program for your specific needs and goals and to help you heal.

In some cases, your physical therapist may refer you for diagnostic imaging. Ultrasound, X-ray, or MRI can help to confirm the diagnosis and find out how severe the injury is.

How Can a Physical Therapist Help?

Your physical therapist will design a treatment plan to help you safely return to your desired activities. Your treatment plan may include:

Patient education. Your physical therapist will educate you about your AC joint and shoulder injury. They will work with you to identify any external factors causing your pain, including the amount and type of exercises and activities you do. Your physical therapist will recommend improvements to your activities.

Pain management. Your physical therapist will address your pain. This may include applying ice to the affected area and other methods. They also may recommend changing some activities that cause pain. Physical therapists are experts in prescribing pain-management methods. These can reduce or eliminate the need for medicines, including opioids.

Range-of-motion exercise. The mobility of the AC joint and shoulder may be limited, causing increased stress on the shoulder. Your physical therapist may teach you self-stretching methods. These can decrease tension and help restore normal motion of your injured joints.

Manual therapy. Your physical therapist may apply hands-on treatments to gently move your muscles and joints. These techniques help to improve movement. Your physical therapist also may use manual therapy to guide your shoulder area into a less stressful movement pattern.

Muscle strength. Muscle weaknesses or imbalances can contribute to problems of the AC joint and shoulder. They also can cause continued symptoms. Based on the how serious your injury is, your physical therapist will design a safe resistance program to aid your recovery. Exercises may include using resistance machines in the clinic and doing exercises to strengthen your core (midsection). You may begin doing exercises while lying on a table or at home on the bed or floor. You then may advance to exercises done in a standing position. Your physical therapist will choose what exercises are right for you based on your diagnosis, age, and condition. They will determine when it is safe for you to exercise on your own at home or in a gym.

Functional training. Once your pain, strength, and motion improve, functional training can help you safely resume more demanding activities. To minimize the stress to the AC joint and shoulder it is important to teach your body safe, controlled movements. Your physical therapist will create a series of activities to help you learn how to use and move your body correctly and safely. These may include retraining your movements and positioning when throwing, swinging a racket, lifting objects overhead, or doing other daily activities.

Can This Injury or Condition Be Prevented?

Accidents happen and it can be difficult to prevent many traumatic AC joint injuries. However, much can be done to prevent the string of events that lead to overuse injuries. Physical therapists can help reduce overuse injuries by:

Teaching you how to properly lift objects overhead at work.

Demonstrating good form for overhead resistance training or sports activities.

Helping you maintain general shoulder strength and motion to safely perform tasks.

Consult a physical therapist as soon as possible if you have persistent constant or worsening symptoms.

What Kind of Physical Therapist Do I Need?

All physical therapists are prepared through education and clinical experience to treat a variety of conditions or injuries. You may want to consider:

A physical therapist who is experienced in treating people with orthopedic or musculoskeletal (muscle, bone, and joint injuries).

A physical therapist who is a board-certified specialist or who has completed a residency in orthopedic or sports physical therapy. This physical therapist will have advanced knowledge, experience, and skills that apply to those who are physically active.

You can find physical therapists who have these and other credentials by using Find a PT, the online tool built by the American Physical Therapy Association. This tool can help you search for physical therapists with specific clinical expertise in your area.

General tips when you're looking for a physical therapist (or any other health care provider):

Get recommendations from family, friends, or other health care providers.

When you contact a physical therapy clinic for an appointment, ask about the physical therapists' experience in helping patients with shoulder pain.

During your first visit with the physical therapist, be prepared to describe your symptoms in as much detail as possible, and report activities and movements that make your symptoms worse.

Further Reading

The American Physical Therapy Association believes that consumers should have access to information to help them make informed health care decisions and prepare them for their visit with a health care provider.

The following resources offer some of the best scientific evidence related to physical therapy treatment for AC joint injuries. They report recent research and give an overview of the standards of practice both in the United States and internationally. They link to a PubMed* abstract that also may offer free access to the full text, or to other resources. You can read them or print out a copy to bring with you to your health care provider.

Frank RM, Cotter EJ, Leroux TS, Romeo AA. Acromioclavicular joint injuries: evidence-based treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019;27(17):e775–e788. Article Summary in PubMed.

Li X, Ma R, Bedi A, Dines DM, Altchek DW, Dines JS. Management of acromioclavicular joint injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(1):73–84. Article Summary in PubMed .

Harris KD, Deyle GD, Gill NW, Howes RR. Manual physical therapy for injection-confirmed nonacute acromioclavicular joint pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(2):66–80. Article Summary in PubMed.

Pallis M, Cameron KL, Svoboda SJ, Owens BD. Epidemiology of acromioclavicular joint injury in young athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(9):2072–2077. Article Summary in PubMed .

*PubMed is a free online resource developed by the National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubMed contains millions of citations to biomedical literature, including citations in the National Library of Medicine's MEDLINE database.

Reviewed and revised in 2021 by Erin Hayden, PT, DPT, board-certified clinical specialist in orthopedic physical therapy, and Stephen Reischl, PT, DPT, board-certified clinical specialist in orthopedic physical therapy, on behalf of the Academy of Orthopaedic Physical Therapy. Authored in 2014 by Allison Mumbleau, PT, DPT, board-certified clinical specialist in sports physical therapy.