An anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear is an injury to the knee commonly affecting athletes, such as soccer players, basketball players, skiers, and gymnasts. Nonathletes can also experience an ACL tear due to injury or accident. Approximately 200,000 ACL injuries are diagnosed in the United States each year. It is estimated that there are 95,000 ruptures of the ACL and 100,000 ACL reconstructions performed per year in the United States. Approximately 70% of ACL tears in sports are the result of noncontact injuries, and 30% are the result of direct contact (player-to-player, player-to-object). Women are more likely than men to experience an ACL tear. Physical therapists are trained to help individuals with ACL tears reduce pain and swelling, regain strength and movement, and return to desired activities.

What is an ACL Tear?

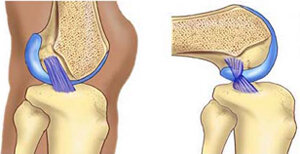

The ACL is one of the major bands of tissue (ligaments) connecting the thigh bone (femur) to the shin bone (tibia) at the knee joint. It can tear if you:

Twist your knee while keeping your foot planted on the ground.

Stop suddenly while running.

Suddenly shift your weight from one leg to the other.

Jump and land on an extended (straightened) knee.

Stretch the knee farther than its usual range of movement.

Experience a direct hit to the knee.

ACL Attachment: See More Detail

How Does It Feel?

When you tear the ACL, you may feel a sharp, intense pain or hear a loud "pop" or snap. You might not be able to walk on the injured leg because you can’t support your weight through your knee joint. Usually, the knee will swell immediately (within minutes to a few hours), and you might feel that your knee "gives way" when you walk or put weight on it.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Immediately following an injury, you may be examined by a physical therapist, athletic trainer, or orthopedic surgeon. If you see your physical therapist first, your therapist will conduct a thorough evaluation that includes reviewing your health history. Your physical therapist will ask:

What you were doing when the injury occurred.

If you felt pain or heard a "pop" when the injury occurred.

If you experienced swelling around the knee in the first 2 to 3 hours following the injury.

If you felt your knee buckle or give out when you tried to get up from a chair, walk up or down stairs, or change direction while walking.

Your physical therapist may perform gentle "hands-on" tests to determine the likelihood that you have an ACL tear, and may use additional tests to assess possible damage to other parts of your knee.

An orthopedic surgeon may order further tests, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), to confirm the diagnosis and rule out other possible damage to the knee.

Surgery

Most people who sustain an ACL tear will undergo surgery to repair the tear; however, some people may avoid surgery by modifying their physical activity to relieve stress on the knee. A select group can actually return to vigorous physical activity following rehabilitation without having surgery.

Your physical therapist, together with your surgeon, can help you determine if nonoperative treatment (rehabilitation without surgery) is a reasonable option for you. If you elect to have surgery, your physical therapist will help you prepare both for surgery and to recover your strength and movement following surgery.

How Can a Physical Therapist Help?

Once an ACL tear has been diagnosed, you will work with your surgeon and physical therapist to decide if you should have surgery, or if you can recover without surgery. If you don’t have surgery, your physical therapist will work with you to restore your muscle strength, agility, and balance, so you can return to your regular activities. Your physical therapist may teach you ways to modify your physical activity in order to put less stress on your knee. If you decide to have surgery your physical therapist can help you before and after the procedure.

Treatment Without Surgery

Current research has identified a specific group of patients (called "copers") who have the potential for healing without surgery following an ACL tear. These patients have injured only the ACL, and have experienced no episodes of the knee "giving out" following the initial injury. If you fall into this category, based on the specific tests your physical therapist will conduct, your therapist will design an individualized physical therapy treatment program for you. It may include treatments such as gentle electrical stimulation applied to the quadriceps muscle, muscle strengthening, and balance training.

Treatment Before Surgery

If your orthopedic surgeon determines that surgery is necessary, your physical therapist can work with you before and after your surgery. Some surgeons refer their patients to a physical therapist for a short course of rehabilitation before surgery. Your physical therapist will help you decrease your swelling, increase the range of movement of your knee, and strengthen your thigh muscles (quadriceps).

Treatment After Surgery

Your orthopedic surgeon will provide postsurgery instructions to your physical therapist, who will design an individualized treatment program based on your specific needs and goals. Your treatment program may include:

Bearing weight. Following surgery, you will use crutches to walk. The amount of weight you are allowed to put on your leg and how long you use the crutches will depend on the type of reconstructive surgery you have received. Your physical therapist will design a treatment program to meet your needs and gently guide you toward full weight bearing.

Icing and compression. Immediately following surgery, your physical therapist will control your swelling with a cold application, such as an ice sleeve, that fits around your knee and compresses it.

Bracing. Some surgeons will give you a brace to limit your knee movement (range of motion) following surgery. Your physical therapist will fit you with the brace and teach you how to use it safely. Some athletes will be fitted for braces as they recover and begin to return to their sports activities.

Movement exercises. During your first week following surgery, your physical therapist will help you begin to regain motion in the knee area, and teach you gentle exercises you can do at home. The focus will be on regaining full movement of your knee. The early exercises help with increasing blood flow, which also helps reduce swelling.

Electrical stimulation. Your physical therapist may use electrical stimulation to help restore your thigh muscle strength, and help you achieve those last few degrees of knee motion.

Strengthening exercises. In the first 4 weeks after surgery, your physical therapist will help you increase your ability to put weight on your knee, using a combination of weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing exercises. The exercises will focus on your thigh muscles (quadriceps and hamstrings) and might be limited to a specific range of motion to protect the new ACL. During subsequent weeks, your physical therapist may increase the intensity of your exercises and add balance exercises to your program.

Balance exercises. Your physical therapist will guide you through exercises on varied surfaces to help restore your balance. Initially, the exercises will help you gently shift your weight on to the surgery leg. These activities will progress to standing on the surgery leg, while on firm and unsteady surfaces to challenge your balance.

Return to sport or activities. As athletes regain strength and balance, they may begin running, jumping, hopping, and other exercises specific to their individual sport. This phase varies greatly from person-to-person. Physical therapists design return-to-sport treatment programs to fit individual needs and goals.

Can This Injury or Condition Be Prevented?

Much of the research on ACL tears has been conducted with female collegiate athletes, because women are 4 to 6 times more likely to experience the injury. Preventive physical therapy programs have proven to lower ACL injury rates by 41% for female soccer players. Researchers have made the following recommendations for a preventive exercise program:

The program should be designed to improve balance, strength, and sports performance. Strengthening your core (abdominal) muscles is key to preventing injury, in addition to strengthening your thigh and leg muscles.

Exercises should be performed 2 or 3 times per week and should include sport-specific exercises.

The program should last no fewer than 6 weeks.

Although most exercise studies have been conducted with female athletes, the findings may benefit male athletes as well.

Real Life Experiences

Anita is a 20-year-old student at a local university, and a star basketball player. Her team is off to a great start this year; the buzz around campus is that this could be a dream team!

But tonight, when Anita goes up for a rebound and lands off-balance, she hears a "pop" in her left knee and feels a sharp pain. When she tries to walk, she realizes that she can't put weight on her left leg. She's led back to the training room, where the school physical therapist conducts an evaluation. The test results indicate injury, and the physical therapist notices an increase in swelling around the knee just 30 minutes after the incident. She suspects an ACL tear, and refers Anita to an orthopedic surgeon. The next day, the surgeon confirms the diagnosis of an ACL tear, and tells Anita that her injury requires surgery.

After a short course of treatment by her new local physical therapist, including pain and swelling management, manual (hands-on) therapy, and knee range-of-motion and strengthening exercises, Anita has surgery the following month. Her surgeon schedules her to receive physical therapy 3 days after her surgery. She is advised to ice and elevate the knee several times per day.

Three days after surgery, Anita returns to her local physical therapist to begin her rehabilitation. He shows her how to use her crutches properly to gently begin to put weight on the operative knee. He guides her to contract/tighten the quadriceps muscle, and gently performs manual (hands-on) stretches for her to straighten the knee.

Over the next few weeks, Anita is able to gradually stop using her crutches, and begins to put her full weight on her left leg. She can also fully straighten her knee and tighten her quadriceps muscle without help from her physical therapist. She learns exercises she can safely perform at home.

After 5 weeks, Anita is able to walk normally, fully extending her knee with no pain or feelings of instability. During the next 2 months, she and her physical therapist work on her strength and balance. She finds the hardest exercises are the balance exercises, which require her to balance on a piece of foam or a rocker board while throwing a ball.

About 4 months after surgery, Anita's physical therapist designs a gentle jogging program for her. At 5 months, he allows her to begin a running program. He also adds exercises during Anita's physical therapy sessions that mimic basketball activities such as rebounding or taking a jump shot. During these activities, Anita’s physical therapist teaches her proper landing techniques to lessen the chance of reinjuring her knee when she returns to play.

After 8 months, Anita is allowed to practice with her team. They are thrilled and excited to see their star player is back. Last year was a good year for the team, but it ended in the first round of the playoffs.

Anita and her team begin a new year of full competition 11 months after her surgery. With Anita back in top form, they make the playoffs, blast through to the finals – and bring home the trophy!

This story was based on a real-life case. Your case may be different. Your physical therapist will tailor a treatment program to your specific case.

What Kind of Physical Therapist Do I Need?

Although all physical therapists are prepared through education and experience to treat a variety of conditions or injuries, you may want to consider:

A physical therapist who is experienced in treating people with orthopedic (musculoskeletal) problems.

A physical therapist who is a board-certified clinical specialist or who has completed a residency or fellowship in orthopedic physical therapy and has advanced knowledge, experience, and skills that may apply to your condition.

You can find physical therapists with these and other credentials by using Find a PT, the online tool built by the American Physical Therapy Association to help you search for physical therapists with specific clinical expertise in your geographic area.

General tips when you're looking for a physical therapist:

Get recommendations from family and friends or from other health care providers.

When you contact a physical therapy clinic for an appointment, ask about the physical therapist's experience in helping people with ACL tears.

During your first visit with the physical therapist, be prepared to describe your symptoms in as much detail as possible, and say what makes your symptoms worse.

Further Reading

The American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) believes that consumers should have access to information that could help them make health care decisions and also prepare them for their visit with their health care provider.

The following articles provide some of the best scientific evidence related to physical therapy treatment of ACL tears. The articles report recent research and give an overview of the standards of practice for treatment both in the United States and internationally. The article titles are listed by year and are linked either to a PubMed* abstract of the article or to free access of the full article, so that you can read it or print out a copy to bring with you to your health care provider.

Nyland J, Mattocks A, Kibbe S, Kalloub A, Greene JW, Caborn DN. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, rehabilitation, and return to play: 2015 update. Open Access J Sports Med. 2016;7:21–32. Free Article.

Anderson MJ, Browning WM III, Urband CE, Kluczynski MA, Bisson LJ. A systematic summary of the systematic reviews on the topic of the anterior cruciate ligament. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4:2325967116634074. Free Article.

Anterior cruciate ligament injury. Medscape website. Accessed June 16, 2016.

Logerstedt DS, Snyder-Mackler L, Ritter RC, Axe MJ, Godges JJ; Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Knee stability and movement coordination impairments: knee ligament sprain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40:A1–A37. Free Article.

Eitzen I, Moksnes H, Snyder-Mackler L, Risberg MA. A progressive 5-week exercise therapy program leads to significant improvement in knee function early after anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40:705-721. Free Article.

Nyland J, Brand E, Fisher B. Update on rehabilitation following ACL reconstruction. Open Access J Sports Med. 2010;1:151–166. Free Article.

Risberg MA, Holm I. The long-term effect of 2 postoperative rehabilitation programs after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomized controlled clinical trial with 2 years of follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:1958–1966. Free Article.

Gilchrist J, Mandelbaum BR, Melancon H, et al. A randomized controlled trial to prevent noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury in female collegiate soccer players. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:1476–1483. Article Summary on PubMed.

Hurd WJ, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. A 10-year prospective trial of a patient management algorithm and screening examination for highly active individuals with anterior cruciate ligament injury: Part 1, outcomes. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:40-47. Free Article.

Benjaminse A, Gokeler A, van der Schans CP. Clinical diagnosis of an anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36:267–288. Article Summary on PubMed.

Hewett TE, Ford KR, Myer GD. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: part 2, a meta-analysis of neuromuscular interventions aimed at injury prevention. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:490–498. Article Summary on PubMed.

Beynnon BD, Johnson RJ, Abate JA, Fleming BC, Nichol CE. Treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injuries, part 2. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1751–1767. Article Summary on PubMed.

Fitzgerald GK, Piva SR, Irrgang JJ. A modified neuromuscular electrical stimulation protocol for quadriceps strength training following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33:492–501. Article Summary on PubMed.

*PubMed is a free online resource developed by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PubMed contains millions of citations to biomedical literature, including citations in the National Library of Medicine’s MEDLINE database.

Authored by Christopher Bise, PT, DPT, MS. Revised by Julie Mulcahy, PT. Reviewed by the editorial board.